A brief look at multiple expansion and its affects on returns.

Buffet doesn't pay up for a reason

A word on value vs growth

We can’t talk about the significance of multiple expansion without talking about value investing more broadly.

Some investors don’t mind paying a lofty multiple for a company, while others are a bit more tight-fisted when it comes to paying for a stock. I tend to feel more comfortable buying cheaper stocks that have the potential to re-rate higher. This is just my nature; I love a bargain. However, I also don’t mind buying a growth stock with a bit higher multiple so long as it’s warranted.

Value investors tend ask the question “For what I’m paying today, what do I get?” They tend to prioritize price relative to earnings or cash flows. Whether they are today’s cash flows or tomorrow’s, the value investor is always paying attention to what the value of the stock is and what they are paying. Value investors are also skeptical of businesses that can only promise to produce cash flows in the future.

Growth investors, on the other hand, tend to ask the question “ What could I get?” put a larger emphasis on the future prospects of businesses and therefore pay much more attention to revenue growth and less attention to the current price relative to cash flows or earning. They don’t mind paying a lofty multiple so long as they believe the company will eventually grow into the multiple and justify the high price.

Have rules but don’t be inflexible

It’s good to be disciplined and have a core set of rules that you invest by.

However, it’s a mistake to totally compartmentalize different investing strategies as if there is no overlap or compatibility between them. Some seem to think that there are deeply defined lines between growth and value, and it is somehow heresy to cross over from one to the other. This is flawed, after all, even Buffett is concerned with both the future growth prospects of a business and the price he is paying for it.

Although I’m a value investor, I’m not overly dogmatic or inflexible. The reason I call myself a value investor is not because I only buy the low P/E stocks, although this is often the case, but because I’m concerned with where the value is.

I do tend to look more for low P/E stocks than high, but I’m also aware that a low P/E does not always indicate a mis-priced stock. In fact, many low P/E stocks deserve a lower multiple than they already have and many high P/E stocks deserve higher.

Nevertheless, I do believe that value can be loosely defined and that generalizations are appropriate. And the evidence does seem to suggest that value outperforms growth over long periods of time.

The case for value

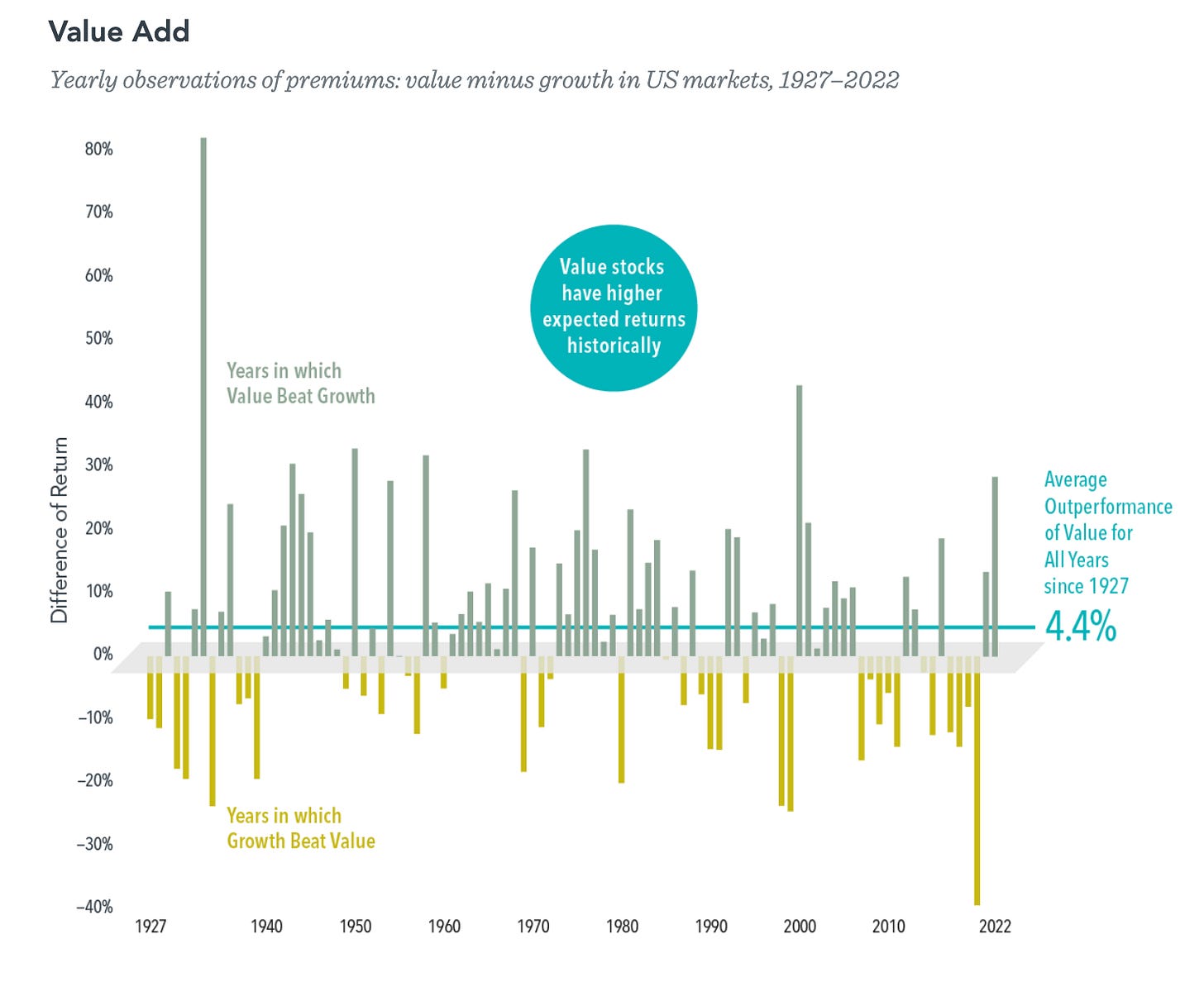

Value has been shown to outperform growth stocks in various different studies. Below is graph from an article by Dimensional Fund Advisors on the historical performance of value investing.

You can see that according to this study, value has outperformed growth by roughly 4.4% on average since 1927. It is clear, however, that since 2008, growth has done quite well, presumably because of lower interest rates. But if you look out over a multi-decade perspective, value begins to pull ahead.

This doesn’t mean that a portfolio of a bunch of random low P/E stocks would have magically outperformed a portfolio that invested in Amazon at the IPO.

These kinds of studies look at averages and large collections of data across time. They don’t account for the unfortunate scenario where someone dumped 50% of their portfolio into a hairball value trap. Nor do they account for the lucky guy who dumped 50% of his portfolio into Amazon at the IPO.

There’s no shortage of value traps that will underperform and or growth stocks that will outperform over the next 10 - 20 years. But in general, if you’re selective and thoughtful, the evidence seems to suggests that value can and will outperform over the long term. And there is sound reasoning behind it.

Here is an excerpt from the article sited above by Dimensional Fund Advisors,

“Value investing is based on the premise that paying less for a set of future cash flows is associated with a higher expected return.”

How true this is.

When you buy a stock, you’re buying a claim on the future earnings of that business. Paying a less for those earnings increases your earnings yield and the odds of a higher market return.

Logically, paying $100 for a stock with earnings per share of $100, produces an earnings yield of 100%. This is better than paying $200, which produces an earnings yield of 50%. That’s simple enough. You don’t need to be a CFA to understand this.

Things get a bit more interesting when earnings grow and or the next investor is willing to pay more for those earnings, which leads us to a discussion on multiple expansion.

Historical returns from multiple expansion

Aside from increasing one’s earnings yield, one of the other reasons paying less for the earnings of a business is to be able to hold the stock as investors are willing to pay more for those earnings. This is multiple expansion.

JP Morgan analyst Meera Pandit explains how S&P returns have partially been driven by multiple expansion over the last 35 years.

“Since 1989, earnings growth has driven 56% of returns, compared to just 25% for multiple expansion and 19% for dividends. However, by calendar year, in 18 of the last 35 years, the contribution from multiple expansion outpaced the earnings growth contribution.”

So, the market has returned around 12.3% per year over the last 35 years, and multiple expansion is responsible for 2.5% of that. Over a 35-year period, that’s actually a huge difference.

Just to put it into perspective, if you were to remove that multiple and only rely on earnings growth and dividends, a $100k investment would have turned into $2.4 million by year 35. But if you were to add back 2.5% for multiple expansion, that same investment would be worth almost $5.8 million, almost 120% more. It’s incredible what an additional 2.5% can do over a long period of time.

A few hypothetical examples of multiple expansion

Obviously, the returns derived from multiple expansion are heavily dependent on the time frame and the total increase in multiples.

Below represents the returns that you would expect from multiple expansion alone over various periods of time. The Y axis represents investment periods between 10 - 30 years. The X axis represents a multiple increase of between 50% - 200%.

If a multiple increases by 50% over a 10-year period, you’d still receive a 4.1% boost in your returns. If it tripled, you’d be sitting on an 11.6% return. Keep in mind, this is on top of whatever returns would be generated by earnings growth.

This brings up another important discussion. Earnings growth combined with multiple expansion.

Earning growth and multiple expansion

I understand that studying multiple expansion alone doesn’t do us any good. No one is ever going to come across a company, with no growth, that expands its multiple by 200% over a 30 year period. So let’s examine something a bit more realistic.

Company B grows earnings modestly at 10% annually for 10 years and at the same time the multiple gradually doubles in that same period from 10x to 20x.

We see that in the early years the returns are more dramatic, but they become more impotent as time passes. However, even with diminishing returns, company B would still have generated a 17.9% CAGR by year 10 on earnings growth of only 10%. The way I see it, the extra 7% - 8% provides you with the opportunity to be wrong and still do okay.

With the added multiple expansion, a $100k investment would be worth $519k. Thats actually really good.

Note: A multiple doesn’t expand in a neat upward trajectory like a magical stairway to heaven. Most likely, it’ll zig and zag, but if the company is perceived as higher quality with a better value proposition, the market will reward the company with a higher multiple over time.

Pros and cons of relying on low multiples for returns

Now that I’ve discussed the connection between value investing and multiple expansion, I want to discus some of the pro’s and cons of these types of stocks.

Pros

Rocket ready: Sometimes when cheap stocks catch fire, the returns can be quite spectacular with minimal risk. Apple traded at 15x earnings in December 2018 (when I took a position), and just 3 years later, it traded at almost 30x earnings. From trough to peak, it was up around 350% as EPS grew, and the market re-rated it higher.

Margin of safety: Often, cheaper stocks represent weak/low investor expectations. When expectations are already low and something unfavorable happens, there tends to be less reaction by the market than when expectation are really high.

Favorable for buybacks: A company with a P/FCF ratio of 10 is able to potentially buy back about 10% of the company. A ratio of 20 reduces this down to 5%. Sometimes companies with low multiples are able to buy back substantial amounts of their stock, which can produce incredible EPS growth and shareholder returns even if growth is minimal. Again, Apple in 2018 - 2021 is a perfect example of this. In that period, revenue grew 38% and earnings grew 59% , however EPS grew 89% because Apple able to reduce their share count. The combination of a low P/E and buybacks can produce amazing returns even if growth is less than stellar.

Cons

Multiples are unpredictable: I try not to put too much faith in the future multiple of a business because it’s hard to predict what the market will pay for a company in the future. I don’t want to assume the market will pay what I want it to. The market can swing from extreme pessimism to optimism, bidding stock prices down and up in a short period of time.

Expansion returns are time-sensitive: Expansion returns are more effective in the short term. Over long periods of time, valuation becomes less important, but never unimportant.

Lofty returns can be taken back: If the market rewards you by doubling the P/E of your stock, it can certainly also punish you by cutting it in half just as quick.

Conclusion

As many investors have pointed out before me, investment returns are driven by some combination of growth, multiple expansion, and cash returns (buybacks and dividends).

Each company you come across may offer a different mixture of these. Some will offer incredible growth with no buybacks or multiple expansion. Others are like fallen angels that are printing cash for buybacks and have the potential to expand their multiple.

Either way, my job as an investor is to look for stocks that could offer greater returns than the market over time. Otherwise, I should just buy the index and spend my time surfing instead of reading 10k’s, like an obsessive nerd.

Thanks for reading! Consider subscribing if you like the content.