The New Financial Capitalists

Part 1: Managerial capitalism and skin in the game

Intro

The New Financial Capitalists, by George P. Baker and George David Smith, is sort of a biography of KKR, but more broadly, it gives a glimpse into the various M&A booms throughout American history, particularly in the 1980’s where KKR made a name for itself. I haven’t finished the book yet but the beginning of the book is certainly interesting. I thought I would summarize it and talk about some relevant topics such as skin in the game.

The book explains how KKR and other “financial capitalists” used various M&A strategies to re-orient corporations towards the interest of shareholders.

Owners and managers

The book carefully examines the history of misalignment between corporate owners and managers. This is traced back to the mid 19th century during the industrial revolution, more specifically in the infrastructure industries (railways, roads, canals).

“A serious divergence between shareholders and managers became apparent in the infrastructure industries, where huge capital requirements led companies to make public equity offerings when their ability to finance expansions from retained earnings reached its limits.”

They go on to explain how board directors, who served the interest of shareholders, would quarrel with corporate managers over how to utilize profits. Owners wanted excess cash flows distributed to themselves after all corporate obligations and “sensible” investment initiatives were funded. On the other hand, corporate managers became fixated on “long term investments” as the industrial revolution brought exciting new opportunities. Managers also became irritated with increasingly “absentee owners” who were absent from operations and yet seemed to be a stumbling block to long term investments.

Managerial capitalism and the rise of technocrat

The industrial revolution brought with it larger corporations that were more efficient and organized. These large corporations were also increasingly complex and capital intensive. This meant that issuing equity would become a more common way to fund operations and as a result corporate ownership would become more fragmented. At the same time, it would also become more common to hire outside “professional managers” to lead these complex organizations.

Unfortunately, often times these professional managers didn’t share the same profit motive as shareholders. Thus managerial capitalism was born.

“Lacking information and expertise in the technical operating details of complex organizations, most shareholders had to rely on the integrity and skill of their hired managers and the ability of board directors to monitor managerial performance”

“As their operations increased in scale and complexity, large corporations became increasingly dependent on a new kind of executive, the professional technocrat. In modern, complex corporations, managers typically became executives because of their strategic talents, technical expertise and organizational experience rather than their familial ties or ownership stakes”

The separation between ownership and management inevitably meant the separation of interests. This divide in interests wasn’t a much of a problem in previous generations because the vast majority of managers were also the largest shareholders, “owners managed and managers owned.”

The divided interests between owners and managers was, at its core, a division between technical “institution builders” and owners who were far more concerned with efficiency. Managers wanted to build empire’s, often times with less concern about risk, while owners were rightfully concerned about unbridled opportunism and potentially wasted capital. Owners ultimately lost corporate influence in late 19th century and excess capacity troubled many business as efficiency became sidelined.

It was under these circumstances that financiers like JP Morgan made their wealth in the late 19th century and early 20th century—restructuring corporations, getting rid of excess capacity and placing shareholder friendly partners on boards. By the 1920’s the second wave of mergers and acquisitions was in full swing—once again aided by investment bankers. Much of this activity died out after the stock market crash in 1929.

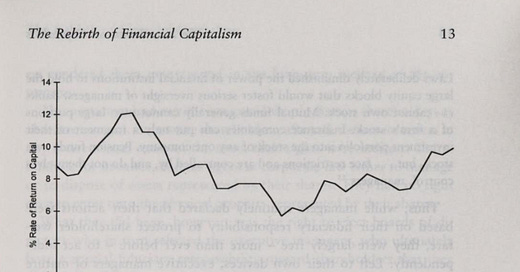

“Managerial capitalism” persisted and became more pronounced in the decades following the second world war. The US economy expanded dramatically and yet returns on capital slowly declined until 1980 as shareholders and profits were once again de-prioritized. Corporate resources were misallocated by increasingly unaccountable and incompetent executives who sought to remove accountability from themselves. Profitability was also burdened by unions who won labor rights and bigger shares of revenues.

“Executives began anointing themselves on boards and placed their subordinates and friendly “outsiders” on their boards of directors. Internally, the ranks of middle managers swelled, as corporate officers grew to accommodate more and more managerial functions—few of which were eliminated when their usefulness diminished”

“Unions won bigger shares of corporate revenues for their members, not only in wages but also in medical insurance, time off, retirement benefits, and automatic cost-of-living adjustments”

By the 1970’s many American companies that were once great had become bloated, complacent and full of middle management. Corporate politics had become a problem that required managers who knew how to manage corporate politics.

“Mature industries at the center of the economy had become largely complacent oligopolies, in which the desire for stability took precedence over profit maximization.”

“Corporate reward systems favored bureaucrats (who knew how to manage corporate politics) over entrepreneurial dissenters (who were more likely to provoke reforms)”

All of this mismanagement once again paved the paw for savvy financial entrepreneurs to intervene and act as intermediaries on behalf of shareholders. This ultimately lead to the wave of corporate takeovers that most of us are probably more familiar with during the 1980’s. This is where companies like KKR made a name for themselves addressing these problems through buyouts and restructuring underperforming assets. Leverage was used to acquire struggling conglomerates and transform their economic condition to re-orient them towards profitability and shareholder value.

Takeaways

I’ll continue in more detail as I progress though the book, but for now I want to talk about a few observations and conclusions I’ve drawn so far.

At the end of the day, KKR and other buyout firms were intervening on behalf of shareholders because corporate managers had forgotten who they ultimately answer to, the owners.

What is a shareholder?

I’m a huge fan of first principals thinking and re-hashing basic principals. This is probably because I’m an intellectual snob and I like to complicate things. As such, I was grateful when the authors of this book gave a fresh reminder of what a shareholder actually is and why they’re important.

I often hear people talk about skin in the game, that is, executive ownership that creates accountability, and I agree this is very important. But what I don’t hear people talk about very often is what it means to be a shareholder in the first place.

I think it’s also often falsely perceived that shareholders are a privileged class of asset owners, but in reality shareholders are the least privileged class in the corporate universe. Shareholders don’t actually have any direct control over the day to day operations of a business, but they do have the right to elect board directors who select executives, who “ultimately bear a special fiduciary duty towards shareholders.”

At first glance it would seem strange that executives have “special fiduciary duties towards shareholders” but the logic is actually very simple. Shareholders are the only people in the corporate universe who don’t have a contractual agreement that must be honored. In other words, employees, creditors and vendors all have legally binding agreements that ensure they will be paid. Shareholders on the other hand, have no such assurance because they only have a residual claim on corporate assets. This means they might receive payments (dividends, buybacks) after everyone else is paid, and they usually get nothing in the event of a liquidation.

Since shareholders have the most to lose, the logic is that they should theoretically have the best interest of the company in mind, namely long term health and efficiency, which would maximize their residual earnings. This is why they are granted voting rights and managers are ultimately work for them. It’s a strangely paradoxical idea, yet practical and democratic.

Skin in the game

Something special occurs when a manager also happens to be a large shareholder. There is a sense of alignment that is just seems right.

I like to think of it this way, imagine a ship sailing the ocean. On board there is a captain, a handful of crew members and a few ship owners, but the owners are chained to the deck of the ship. In the event of a shipwreck, the owners would not only lose their ship—they’d also be dragged to the bottom of the ocean floor as it sunk. This stark reality instills in the owners a unique sense of risk management and a particularly strong desire to ensure the ships safety.

If the captain and the crew members weren’t chained up they could easily abandon the ship in the event of a wreck and float to shore on a life boat. For them, a ship wreck would be unfortunate, but nothing compared the devastation the owners would endure. However, if the crew members and captain were also chained to the ship, you could be certain that they would take every precaution possibly to ensure the long term safety of the ship.

Moral of the story, If I’m going to be dumb enough to chain myself to a ship deck, I want to be certain my captain is wearing that chain too.

Conclusion

As an investor I want to be mindful of blatant “managerialism” and “empire building.” I don’t want to ride the coattail of a CEO who’s trying to be the king of the world. I want leaders who have a strong incentive to grow the long term economic value per share and manage capital wisely. I want honest leaders who are willing to chain themselves to the ship deck as well. This is the way.

Thats it for this week thank you for reading!