Return on capital is often discussed in the value investing community, and for good reason. It’s actually somewhat confusing considering how many different ways there are to calculate it.

Regardless of the calculation, return on capital attempts to measure how efficiently a company can turn a profit with the resources on its balance sheet. This is expressed as a return on investment because those resources are invested in the company and they ultimately convert into earnings, of so one should hope. The ideal company invests nothing and increases its profits into eternity. Unfortunately this isn’t possible in the real world, businesses must invest capital in order to produce capital.

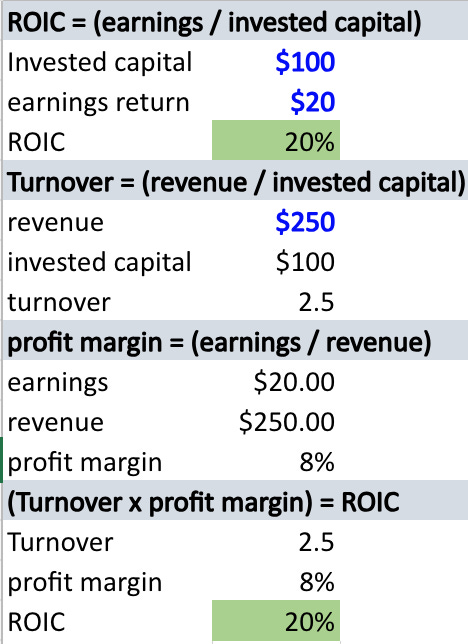

I recently read an article by Mercer Capital that talked about return on invested capital (ROIC) as two components, which really helps to clarify what ROIC is conceptually. It’s similar to the Dupont analysis, which some of you may already be familiar with.

ROIC = turnover x profit margin

If you really think about it, ROIC tells a story that begins on the balance sheet and ends at the bottom of the income statement. Technically, it ends at the bottom of the balance sheet as well as the income statement and the balance sheet are connected via retained earnings, which is a component of the equity portion of the balance sheet. However, the income statement is more helpful in this analysis.

It’s best to view this journey in two stages.

Invested capital is converted into sales, which is called turnover. Invested capital is calculated from either side of the balance sheet (debt+equity) or the asset side.

Costs and expenses are debited and a profit remains, revealing a profit margin.

Let’s break this down and then go through a hypothetical example and then some real-life examples.

By the way, for the sake of simplicity, the numerator and denominator in ROIC are represented by earnings and debt + equity. Maybe I can get into the different variations of the formula in a different article.

Turnover = (revenue / invested capital)

Profit margins = (earnings / revenue)

ROIC = Turnover x profit margin

Hypothetical company

Here is the financial data for our hypothetical company.

$100 invested into the business

$20 in earnings

$200 in revenue

Below is a model for understanding this scenario. The top section and the bottom section are the same thing expressed differently, which is why the ROIC figure are the same. The middle two sections represent calculations for turnover and profit margin.

I think it’s useful to look at it this way because the first part (turnover) measures how well resources are allocated in order to fund the operations, and the second part (profit margin) reveals how efficiently they manage and control costs.

Turnover

This particular formula for turnover is similar to the capital turnover ratio except that it includes debt. It tells us how much total capital is needed to drive sales. It also reveals, to some extent, how well management allocates capital. A higher turnover ratio means more revenue is generated from each dollar that is invested into the business. This isn’t perfect for all companies but it gives us a rough idea.

Profit margins

I’m sure we all know this, but profit margins can help us understand how efficiently a company turns revenue into profit. A higher profit margin indicates that the company has control over its cost and pricing power.

Let’s go through a couple real life examples.

Here are three very different companies with different margins and turnover ratios, but similar ROIC. Note: This is from 2022.

Clearly Autonation had the best performing capital—likely because the price of cars has increased so much—and yet they had the worst profit margins out of the group. They busted out $4.49 in revenue for every dollar invested, but out of every $4.49 in revenue, they only kept 5%, or $0.23. In other words, for every dollar invested, the company generated a bottom line return of roughly 23%.

McDonalds on the other hand is only churning out $0.76 in revenue on each dollar invested, and yet earning a 26% on that (No wonder… they charge $0.99 to add “cheese” to your McGriddle!) The end result is a return of roughly $0.20 or 20%

Each dollar Pultegroup invested turned into $1.41 in revenue and they were able to keep 16% after all expenses. The result was also roughly a 22% return on invested capital.

Each of these companies generated a similar ROIC, at least in 2022, but with very different business characteristics.

Now, I haven’t done deep dives on these companies, but a quick look at their financials and a little intuition tells me McDonald’s likely has a low turnover ratio because it has a ton of debt and real estate on its balance sheet, which increases its invested capital relative to its revenue. They also have high profit margins because they keep their costs low while marking up their plastic cheese by 100,000%. I’m kidding; I don’t know their mark-up, but you get the picture.

Autonation was able to turn a lot of revenue, especially recently as car prices have increased over the last few years. But unfortunately they weren’t able to keep much of that revenue because of large expenses such as the cost to purchase the cars they sell.

Pultegroup is somewhere in the middle. Home builders are usually asset heavy because they have a lot of land tied up on balance sheet (50% of their homes sold are from land inventory they own). Regardless, Pultegroup, along with the other builders, are able to earn decent profit margins, especially over the last few years as home prices have increased.

Which part is more important? Turnover or margins?

Every business is working with a different set of requirements and a different cost structure. At the end of the day, both are important, and I want a company that is able to extract large profits from growing revenue while limiting the capital invested for that growth.

Money in money out

What really matters is total dollars invested relative to dollars earned. So a lower profit margin could be completely fine so long as a smaller amount of capital was invested to get it. Or put another way, big fat profit margins aren’t all they are cracked up to be if they must be constantly maintained by large capital investments.

To illustrate this point, here’s a quick example of two hypothetical companies: Company A has a higher profit margin (5% higher) but also requires twice as much capital to grow the business; Company B, on the other hand, has a lower profit margin but needs half as much capital to grow. B still wins despite the lower margins.

Conclusion

I’d love to find the best of both worlds: businesses that are able to grow earnings with minimal capital investments and limited operating expenses, or outsized earnings in comparison to both. This is really what investors should be thinking about over the long term. These types of companies are rare and usually priced to perfection, but occasionally the market offers them at reasonable prices. I don’t know about you, but I want to be ready to buy.

Thanks for reading!