NVR

NVR is on sale

Key information

Investment type: Quality/value

Ticker: NVR

Market cap: $21.5 billion

EPS: $484

P/E: 15

FCF yield: 6%

Historical 5 year CAGR: 18.5%

Potential 5 year return: 5% - 105%

Why this opportunity exists: Industry pessimism, market discounting long-term tail winds in the building industry.

Intro

I usually hesitant to write about companies that have been covered so many times by other analysts and writers, and NVR seems to fall into this category. However, many of the home builders, including NVR, have fallen 30% - 40% since their high in September which could present an opportunity.

There are other home builder stocks that are interesting as well such as D.R Horton, PulteGroup and Lennar. However, this article will be about NVR.

NVR overview and history

NVR is a home builder that focuses on single-family detached homes, primarily on the east coast and midwest. Over the years, NVR has become an investor favorite because of its high returns upon capital and incredible results. What’s even more intriguing, however, is the companies story of ruin and revival.

In the 1970’s Dwight C. Schar was serving as Vice President of Ryan Homes, a leading a single-family home builder operating in the Washington D.C. area. Schar went on to found NVHomes L.P. in 1980, which would compete with Ryan Homes and eventually acquire it. NVHomes grew rapidly throughout the 1980’s, doubling income each year and acquiring large plots of land to get ahead of price increases in their key markets.1

By 1986, high growth in GDP and a devaluing dollar in the FX market prompted the federal reserve to begin raising interest rates over concerns of inflation, which would put pressure on the economy. 2 In an economy already on edge, the invasion of Kuwait in late 1990 shocked the markets. Oil prices increased dramatically and consumer confidence went down the drain, dragging the economy, the housing market and home builders down with it.

NVHomes (later rebranding NVR L.P.) was no exception. The company took a beating—reporting a $261 million loss in 1990. The earnings loss was largely due to an inventory write-down on their land, land that had a fair value worth less than what they paid for it. Heaping land onto the balance sheet in the 1980’s may have seemed like an intelligent move, but it proved to be problematic in the early 1990’s when land prices began to decline, leaving a serious dent on the balance sheet of NVR.

To compound its problems, NVR was levered to the teeth from acquiring so much raw land for development, a process which can take years to get a full return on investment. Of the $850 million in total debt on NVR’s balance sheet, $218 million was high yield debt that they issued to acquire Schar’s previous employer, Ryan Homes. High debt repayments began to put pressure on NVR as home sales dropped 50% in one of their key market, Washington D.C. 3

By 1991, NVR’s home building revenues had been cut in half, and they began restructuring the operation in several ways, including exiting certain markets and closing several manufacturing plants. Despite efforts to cut costs and restructure, NVR was not able to service its debt and sought protection from creditors (bondholders) as it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1992. They continued to pay their bank debt but stopped paying their bondholders completely during this process.

Emerging as a new company

They emerged from bankruptcy in late 1993 and agreed to turn corporate control over to bond holders. Bond holders received a 91% stake in the company and the former partner holders received 6% of the newly formed company. 4 NVR Inc. went public in September 1993 and boy-o-boy, considering the stock trades at 7,300 today, that would have been a great time to buy some shares of NVR under $10.

The most important thing about NVR’s bankruptcy is the lessons that were learned and the changes made to NVR’s operating strategy. Above all else, Dwight Schar learned that a successful builder must be able to sustain itself in times of economic hardship. He began to re-orient NVR towards a “land-light” model, a model that would gradually be adopted by almost all large public builders over time.

Land-light

Following the bankruptcy, Schar reasoned that NVR must have plenty of capital (and low debt) on the balance sheet if it was to sustain downturns in the future. But of course, this wasn’t possible if NVR was to be involved in developing raw land. He concluded that land development should be outsourced to a third party who could sell it to them on a set schedule. By contracting with land developers or land banks, NVR could not only avoid the carrying costs and development costs but also avoid the risk of holding depreciating land in a downturn. A more appropriate name for this business model could be “inventory-light” because the land inventory is carried by a third party who bears the risk.

In this model, NVR would instead pay a small upfront fee to land developers of around 5% - 10% of the cost of land. In return, the developer would agree to develop the land and sell it to NVR at an agreed upon price in the future. For every dollar that was previously spent on land development, NVR would now spend only $0.10 not to acquire, but to secure control over “build ready” lots. Now that the cost to control land was reduced, they could control much more land at a fraction of the price, which is one of the greatest benefit of this model. These agreements are called lot purchase agreements (LPA’s) or lot option contracts.

The LPA would give NVR the right to buy the land but not the obligation. In the case of an economic downturn where demand softened, they could forfeit their 5% -10% fee and refuse to buy any more land, therefore making the operation more nimble.

Now, it’s worth noting that this isn’t some magical risk-free land acquisition strategy. There are always risks with any strategy. James Brickman, Co-Founder of Green Brick Partners, has been an outspoken critic of this strategy on occasion—seeing it as having been oversold by Wall Street, and a strategy that has enriched bankers at the expense of builder gross margins. I can get into more detail about this in the risk section.

Pre-sold homes

Another key change that occurred was when NVR stopped building spec homes and began building homes on a “pre-sold” basis, meaning that construction wouldn’t start until after a customer had a mortgage approved and a home was sold. Traditionally, builders choose to build at least a portion of their homes on spec. If you aren’t familiar, spec is short for speculation, and it’s where homes are built based on regional trends/styles, and then hopefully sold to a customer who likes it.

NVR rejected this model and decided not to build anything until a home was sold. This meant that any finished homes or homes in progress were already sold at a predetermined price, minimizing the chances of having unsold finished home inventory or inventory write-downs. The biggest cost they incur in a downturn is the forfeiture of the lot purchase agreement fees, and this would only occur if they refuse to acquire the lots under contract.

Buybacks

Post-bankruptcy NVR also Now that NVR was outsourcing land development, it had a favorable working capital improvements that contributed to increased cash flows—cash flows that could be used to repurchase shares, a discipline that has continued to this very day.

Since 1996 NVR has reduced its total shares outstanding by 80%. As of 2025 NVR has less than 3 million shares outstanding. I want to zero in on the financial crisis for a brief moment.

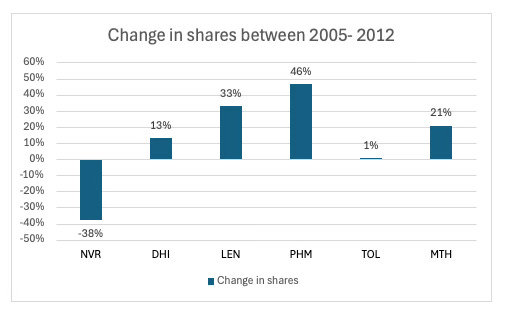

I will talk more about buybacks in the management section, but first I wasn’t to point out what NVR was doing in the period between 2005 and 2012, which is really a fascinating period to study this industry. Home builders made money hand over fist leading up to 2006 and then suddenly found themselves in deep water by 2007 and really didn’t start to recover until 2012-ish.

In this period, NVR was buying back its own stock at a breakneck speed, while other builders were issuing equity and diluting shareholders just to stay afloat. It was like a downward spiral as earnings/margins decreased and shareholder were diluted. However, NVR impressively reduced its shares outstanding by 38% in that period.

Market leader

A big part of NVR’s strategy post-bankruptcy has been focusing on becoming a market leader in whatever market they’re in. The reasoning for this is fairly intuitive. Home builders must contend with physical limitations that make efficiency and scale very difficult. At first blush, this may seem like a liability, but in reality, it contributes to a unique competitive advantage.

Unlike the digital world, much of the efficiencies in the home building industry are predicated on proximity. When I was in contractor school, I was taught that on any given project, 60% - 70% of the time will be spent simply transorting and handling materials. I actually believe this figure is higher. Large material orders must be loaded up and shipped, and then they must be unloaded and strategically placed/stored on site to accommodate the progression of the project; otherwise, they will get in the way and need to be moved. Workers inevitably travel to local hardware stores and suppliers often to get extra, forgotten, or last-minute items. And then of course, materials are constantly moved and handled on-site as things as they are installed and assembled. I say all this to note that there is a very real sense in which proximity and locality matter in the industry, and how a company handles their materials impacts their efficiency dramatically.

It follows that regional concentration is critical to scale efficiently. Although this is well known and applied by all of the public home builders, NVR has been particularly good at squeezing efficiencies out of their operations by concentrating in certain markets, which allows them to spread fewer resources across more projects.

The primary way that they do it is through organizing their building operations around strategically placed and centralized manufacturing facilities. NVR’s aim with these manufacturing facilities is to limit the transportation and handling of materials and get the most productivity out of resources.

“We use a method of construction called panelization. Panelization allows for the building of large portions of our homes in ten centralized production facilities.”

“We produce large portions of our homes in our centralized production facilities, including wall panels, roof trusses and stairs, which allows us to reduce waste, effectively recycle materials, and improve accuracy and consistency in our construction. Our production processes use computer-driven saws that maximize the use of raw lumber to fabricate roof trusses and wall panels, resulting in an extremely low waste factor.”

- 2025 NVR Proxy Statement

This obviously limits on-site measurements, saw cuts, clean-up, and waste for the contractors on-site, but more importantly, it allows NVR to manufacture homes in a centralized production style. Not only is this a much quicker way of manufacturing building components, but a much quicker way of delivering materials to the job site and a much more efficient way of assembling them.

One truck could potentially deliver pre-fabricated components to multiple projects within a relatively close proximity of each other, allowing them to service more projects with fewer trips and resources. For example, in Richmond, Virginia, they save 165,000 gallons of fuel annually just from the efficiency of their facility there.

“Our production facility in Richmond, Virginia, will save approximately 165,000 gallons of fuel annually due to its proximity to our communities.” - 2022 proxy statement

Once the wall panels are delivered, they can be assembled together to form the outer walls, interior walls, and finally the roof. This stands in contrast to the traditional way of building, where raw materials are delivered to the site and then fabricated, most often on the ground, with very limited space, and with much prep and clean-up before and after.

Another way that their market concentration is beneficial is by spreading sales, general, and administration costs across projects. NVR may have supervisors, sales teams, engineers, and other personnel on multiple projects within a few miles or minutes of each other, making site visits cost-effective and getting the most out of personnel.

NVR subcontracts virtually all of their building labor to smaller building contractors who work under fixed-price contracts, meaning they undertake it at a fixed price rather than hourly rates. It’s worth mentioning that most public builders subcontract their entire building process now largely due to very high workers’ compensation insurance rates. By outsourcing to subcontractors, the prime contractor (NVR in this case) is able to pass those burdens onto the subcontractors who have to carry their own insurance for their employees.

Circling back around to regional concentration. I can only speak from my own experience as a remodeling contractor, but in general, subcontractors are willing to bid their rates lower when someone provides projects that are consistent and in close proximity to each other. For example, a contractor who is hired to install cabinets in 100 homes in one particular region will logically charge less than a contractor who will do the same in two regions.

Now this is not necessarily unique to NVR because all home builders understand this dynamic, but by concentrating in a few markets, NVR is able to provide consistent work for contractors in markets they’re located in. Over time, those contractors presumably become loyal partners—offering lower pricing because they don’t have to spend on marketing to acquire work, nor do they don’t need to spread their crews, tools resources over multiple regions.

Lastly, NVR is able to gain bargaining power and procurement benefits by having centralized manufacturing facilities.

“Our centralized production facilities enable us to have significant control over the sourcing of raw materials. For example, lumber is one of our most important raw materials, and centralization allows us to purchase a significant amount of lumber from sustainable forests.”

Now, admittedly, this is an excerpt from the proxy statement concerning sustainability rather than efficiency. Regardless, I think the argument still stands. Rather than ordering raw lumber to be delivered to 5-10 different markets where communities are being built, they can order in bulk to be shipped to one centralized production facility, likely saving them on procurement and shipment costs.

All in all, I think the key thing to understand is that while all builders benefit from regional concentration, NVR is able to maximize these benefits by prioritizing market leadership in a few markets rather than exposure to many. Just for comparison, KB Homes is a similar size builder with almost identical revenue, and yet operates in 60 markets while NVR only operates in 36. KB Homes, which is a smaller competitor, operates in 47 markets.

So, the general strategy with NVR is quality not quantity, and I think this is a principle that is found everywhere in the business, not just in their regional strategy.

NVR’s results

Today, NVR is one of the largest and most efficient home builders in the US. They’ve compounded earnings per share at 21% over the last decade and, more importantly, have best-in-class returns on capital, which was an unintended consequence of having much less inventory on the balance sheet. Schar didn’t change the operating model for the sake of higher returns; he did it out of necessity and risk management. The high returns were an organic byproduct.

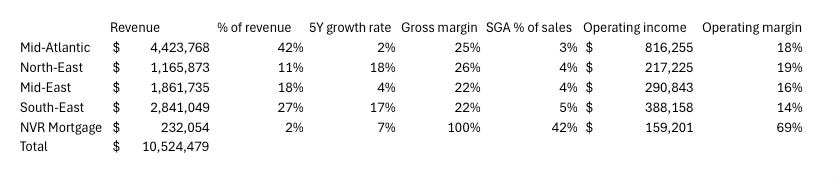

NVR primarily generates revenue from its home building operations. Below are the regions they operate in, the revenue share and annualized growth over the last five years, along with margins and SG&A expense as a percentage of revenue.

Mid-Atlantic: Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware and Washington, D.C.

North-East: New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania.

Mid-East: New York, Ohio, Western Pennsylvania, Indiana and Illinois.

South-East: Consists of North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia and Kentucky.

Mid-Atlantic is NVR’s largest and most mature segment and it’s where they’ve operated the longest. Mid-Atlantic has seen slower growth but is more efficient with higher margins and lower SG&A. South-East in another big segment, but it has seen much growth due to a large population influx into the region over the last few years. South-East’s margins are noticeably lower and SG&A is larger relative to sales.

NVR also has a mortgage operation that generates revenue from fee’s and gains on sales of loans and title fees. This is clearly more profitable with operating margins at 69%, but is also a very small portion of revenue. This segment serves as an aid the their building platform.

Inventory turnover

Although NVR does not crank out as many homes per year as competitors who use more leveraged and own land, they have been able to turn over inventory rapidly once it is on the balance sheet. The land does not touch the balance sheet until a home is sold and then the home is built in a very efficient manner, resulting in high turnover.

By dividing the cost of goods sold by the average inventory we can see how efficiently a builder is able to turn raw land inventory into revenue. A higher number implies that a builder is able to do this much faster and more efficiently. Below you can see that NVR is leagues ahead of every other major builder. Dream Finders Homes is closing in on NVR because they operate a similar model to NVR.

The easiest way to think about this is that NVR turns its inventory about 4 times per year. If we divide the number of days in a year (365) by the figures above, it reveals how long inventory is held by these companies on average. All else equal, high turnover and low days outstanding indicate very good inventory management. Below you can see that NVR holds its inventory for just under 100 days, which is about the time it takes NVR to build a home.

Revenue and earnings growth

While NVR’s revenue growth has lagged competitors, increasing returns on capital and a reduction in shares outstanding have afforded them EPS growth of 21% annually over the last decade. This is not as fast as some competitors such as PulteGroup and D.R. Horton, who grew EPS at 30% and 24%, respectively, in the same period. However, earnings growth alone says little about how well a company uses its cash flows, nor does it say anything about what investors are willing to pay for those earnings.

It’s also worth mentioning that D.R. Horton and Pulte—and others major builders— still engage in land development (25% and 44% of homes sold for D.R. and Pulte), which presents slightly more risk.

While there is some debate as to whether a land-light strategy is truly optimal, most major builders have incrementally moved away from traditional land acquisition strategies in favor of the land-light model. In my view, this implies there is something valuable about the strategy.

Leverage

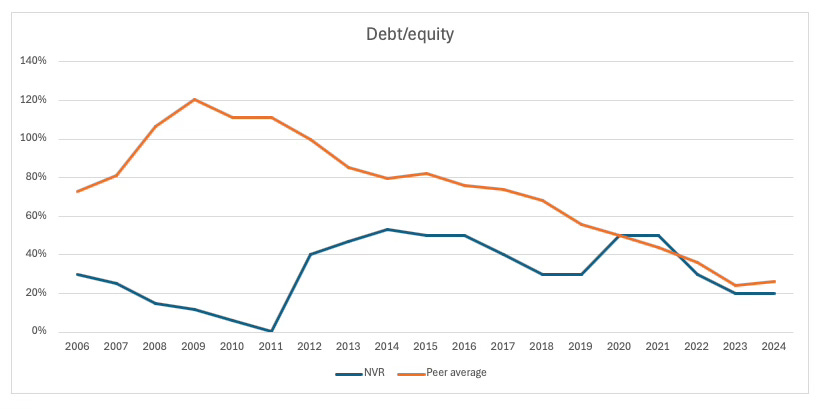

Builders began leveraging up during the housing boom preceding the 2007 Financial Crisis but then found themselves forced to suddenly leverage up even more (and issue equity) as the housing market imploded in 2006 and they fought to survive. NVR, however, was not only able to buy back shares as I previously mentioned, but was also able to deleverage its balance sheet going into the housing crisis while peers were loading up on debt. Below you can see NVR’s historical total debt as a percentage of equity compared to the average of a basket of peers.

For the next few analyses, Peers = Lennar, D.R. Horton, PulteGroup, Meritage Homes, Tol Brothers, and KB Homes.

While most builders have deleveraged over time, which is good, you can see that NVR has almost always maintained a lower ratio of debt-to-equity than peers. They maintain similar levels of debt toady as they did in 2007.

Return on capital

Another area where NVR clearly shines is return on capital.

The reason NVR is able to generate higher returns is found primarily in their turnover, as previously mentioned, and secondarily in their cost efficiency.

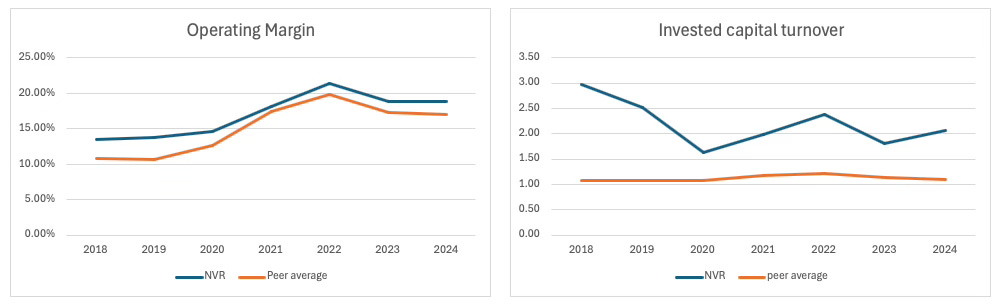

If you think about it, the two large drivers of return on invested capital are capital turnover and operating margin.

Turnover: The amount of revenue generated from each dollar invested (Revenue / Invested capital)

Margin: The percentage of that revenue that is kept by the company in the form of operating profit (operating margin). Of course, we use a post-tax operating profit (NOPAT) figure in ROIC, so the tax rate also affects the numerator, but in general, operating margin is the most important factor.

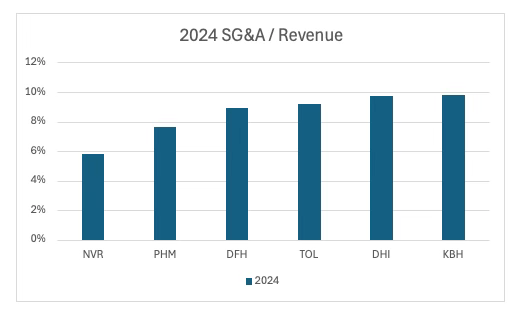

NVR has slightly higher operating margins than peers. This is a function cost discipline and lower SG&A expenses, which are on average 7% of revenue compared to 10% for competitors over the last 10 years.

SG&A as a percentage of revenue is an important figure for homebuilders. SG&A involves things that are more within the builders control, such as sales and marketing strategies, realtor commissions, land development strategy, division and regional management and back office expenses. G&A are primarily a fixed costs that are more centralized and spread over multiple projects. These can remain even if revenue slows down in a bad season, which is not good. G&A also sometimes remain flat when revenues grow— creating a kind of operating leverage. Sales expenses, on the other hand, tend to fluctuate more with revenues because they are tied to realtor and salesman commissions, which make up a large portion of the home sales.

NVR’s low SG&A is likely due to market and regional concentration which requires less regional management and back office expenses, which allows for more G&A leverage. It also likely flows from their hesitation to constantly scale into new markets which requires increased sales personnel. It’s not that NVR doesn’t move into new markets, it’s just that it isn’t a primary focus.

NVR’s SG&A only made up 3% of their revenues in their Mid-Atlantic segment, and 5.8% for their overall operation in 2024, which is phenomenal. Compare this to competitors last year who were up between 8% - 10%.

All this equates to higher operating margins. (Figure D below)

NVR can also generate more revenue from less invested capital (Figure E below) because they have less inventory at any given time. Below you can see NVR has a higher capital turnover— generating more revenue on every dollar invested. While competitors have generated roughly a dollar for every dollar invested, NVR has generated between two to three dollars.

The result is that NVR averages much higher returns—almost twice as much as peers. This of course, is the real reason NVR is so loved by the investing community.

Management

Dwight Schar

Dwight Schar is an incredible businessman. Although he stepped down as CEO in 2005, he remained chairman of the board until 2022 until he decided to fully retire. Before we move on, I want to point out something that highlights the exceptional capital allocation skills of Dwight Schar. What I’m about to say would almost seem like fiction if there weren’t proxy statements to confirm it.

As I went through every post-bankruptcy proxy statement, I stumbled on something. Schar owned 868k shares of NVR in 1997, which implied a 6.8% equity stake. By 2006, his interest had grown to 8.4% despite selling 45% of his shares. For the astute follower of NVR, this is no surprise. For those who don’t understand how share buybacks work, this is probably confusing. Put simply, share buybacks reduce the number of outstanding shares in the company, leaving existing shareholders with a larger slice of the pie and increasing earnings per share. Schar had basically reduced NVR’s share count by 50% in just 9 years.

This period was quite the run for NVR in terms of growth in earning per share and stock performance. Shares were trading at around $20 - $30 in 1997, and grew to around $600 by year-end in 2006. NVR earned $1.72 per share in 1997, but after buybacks and earnings growth, it earned $110 per share, a whopping 6,200% increase, or a 59% annually.

In my view, this really highlights the importance of getting behind talented management. And although Schar is no longer involved with NVR and has basically sold all his shares, his legacy lives on, and one of his early partners, Paul Seville, is still involved with a large stake in the company.

Paul Seville

Paul Seville was the CFO of Ryan Homes before it was acquired by NVR. Paul Seville became CEO of NVR after Schar retired in 2005. Seville oversaw the company’s incredible growth and led the company during the Great Financial Crisis where NVR remained profitable while all other builders did not. Having spent many decades with the company, Seville understood NVR and Ryan Homes better than anyone and learned from the best. In 2022, Seville became chairman of the board but stepped down from CEO as Eugene Bredow took his place.

Seville’s shares ownership has increased over the years as well. In 1997, Seville owned 186,796 shares representing 1.5% of the company. Today, he owns 170,769 representing a 5.4% total interest with a value of about $1.3 billion.

The current CEO, Eugene J. Bredow, owns 19,666 shares of NVR worth roughly $140 million, which is many multiples more than his base salary of $ 1.25 million. Although Bredow’s stake in NVR is less than 1%, it’s enough to incentivize him. I am interested to see how his ownership grows over time.

Risks

Below are a few key risks I see with NVR

Soft demand: Although long term tail winds are in tact, short term housing demand is softening and could continue to soften for the foreseeable future due to lack of affordability, low supply and higher mortgage rates.

Increasing options pricing: This doesn’t get discussed often, but it’s something I think about often. Land developers and land bankers aim to maximize their profits, and almost all the public builders are moving towards a land-light model, presumably because Wall St. likes it. One can only assume that lot option pricing would increase as demand for them increases, which could put pressure on the gross margins of those builders that primarily use a land-light model. Green Brick Partners CEO spoke about this last year on their quarterly call.

“because some builders are trying to stay land-light no matter what because of what they told Wall Street, they're paying prices for lots we would never consider on an option basis” - James Brickman Q1 2024 quarterly call

Lack of skilled construction labor: There has been a lack of skilled labor in construction since the great financial crisis. This strains production capacity. Without getting into political discussion, it should be noted that over half of foreign born construction workers are undocumented.5 It’s estimated that almost 25% of total construction labor is undocumented. Although it’s unlikely, deportations could potentially rid the US of 1.8 million undocumented workers.6 While this would be positive for legal worker wages, it could, in theory, further strain production capacity.

Financials and valuation

As we’ve already seen, NVR has low leverage and high operating margins. Unlike virtually all other builders, NVR also has a net cash position of $1.6 Billion ($2.5 bn. cash - $911 mm. debt). NVR also cranks out $1.3 billion in free cash flow, implying around 16x Free cash flow, or 6% FCF yield at current prices. NVR has a very good quality of earnings and robust free cash flow conversion of 80%.

If there is a recession in the near term, NVR is positioned to begin taking market share an acquiring competitors. This explains why NVR trades at 15x earning rather than 6-10x like competitors.

For the valuation I’m making a few assumptions

Bear and base case reflect weak growth for 2025 and 2026 before picking up again. Bull reflects a continue growth trend in new housing and similar historical revenue growth.

Pretax margins between 19% - 21%

Continued annualized share reduction of 2.5% - 3.5% annually from buybacks (2.6% =10Y average)

End multiple of 12x - 15x

Final thoughts

NVR is arguably the best home builder to ever do it. NVR shareholders rightfully see themselves as partners and business owners and they are treated very well by management, who are also shareholders.

There’s no doubt that I would consider buying the stock at the right price. However, at this time I’m going to pass because I already own another home builder and don’t want overexposure to the industry.

That’s is for this week, thank you for reading!

Disclaimer: Nothing I say should be taken as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor so please do your own research. None of my financial models should be taken as buy or sell signals. Some stocks I discuss are very risky. Please consult a financial advisor before buying or selling any securities.

Full disclosure: I am not a NVR 0.00%↑ shareholder at the time this was written.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/books/politics-and-business-magazines/nvr-lp

https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2023/eb_23-26#:~:text=Rate%20Cycle%3A%201987%2D1992&text=In%20its%20first%20meeting%20in,5.9%20percent%20to%209.8%20percent.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/08/22/home-builder-nvr-posts-a-loss-of-535-million/f36f41d0-995f-47d3-be36-5a9cad33699a/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1993/09/30/nailing-down-nvrs-remodeling/8e7be483-24cb-4aec-9eaa-884a0017a689/

https://cmsny.org/publications/climbing-the-ladder-052322/

https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/mass-deportations-would-worsen-our-housing-crisis#:~:text=The%20Center%20for%20Migration%20Studies,1.8%20million%20undocumented%20construction%20workers.

Thanks for the write up! You included some history I didn't know. I focused a bit more on unit economics and how their ASPs have trended compared to national averages: https://beelicapital.substack.com/p/nvr-inc

Don’t you think relying solely on land options isn’t the most efficient strategy? After all, they aren’t free—and if you end up canceling 100% of them, you’re not building anything at all.

Personally, I think a more balanced approach makes sense: owning lots for your core pipeline while using options for the more speculative projects. That seems like a healthier model.

Sure, companies like NVR and DFH have done well recently using options—but how much of their success can we really attribute to that strategy alone, versus other strengths they might have?

And isn’t it possible that in certain macro environments, owning land outright could actually be better? For example, if developers aren’t needing to cancel options, doesn’t that suggest they’re getting land at more attractive prices—and maybe those using only options are missing out?